finally time for a new carburetor

Moderator: Site Administrators

-

landon1

- GTX (RS)

- Posts: 1391

- Joined: Tue Dec 27, 2005 10:22 pm

- My Cars: 1971 Plymouth Satellite Sebring

- Location: Colfax, IA

finally time for a new carburetor

hey guys...i finally am able to get a new carb for the satellite...we had a long string on the thermoquad and how great it would be for mileage and performance....i can get a factory remanufactured one for about 200 bucks...

however edelbrock has a factory rebuilt performer carb for about the same price...does anybdoy have experience or have heard of how these carbs do as far as gas mileage and performance as well...it's going on a 440, so it will be a 750cfm.

thanks

however edelbrock has a factory rebuilt performer carb for about the same price...does anybdoy have experience or have heard of how these carbs do as far as gas mileage and performance as well...it's going on a 440, so it will be a 750cfm.

thanks

-

73 runner

- Satellite Sebring (RH)

- Posts: 57

- Joined: Sun Feb 06, 2005 6:04 am

- Location: vancouver,bc canada

Hey there Landon1, I too had the thermoquad on my 73 Roadrunner 400. It came to the point that the plastic caseing and other parts were getting worn over the years. Even the rebuilt kits were good for awhile but over a period it just was not performing right. A buddy of mine suggested to install a new Edelbrock performance series 800 cfm with the electric choke, and a halve inch spacer. After he did some minor adjusting, that bone stock 400 came to live with another 10-20 hp! What a difference it made, the added bonus was the faster warm up with the electric choke. So my experience is, go for that carb.

My personal experience is stay away from the edelbrock. The gas drains or evaporates very quickly out of the bowls making it hard to start after only a few hours. Also, I've always had a bog with mine that I can't get rid of.

AKA Butterscotch71....the road runner nest is out to win you over this year!

- mopar71

- GTX (RS)

- Posts: 1097

- Joined: Sun Dec 14, 2003 11:55 pm

- My Cars: 1971 roadrunner

- Location: Milford,PA

Eric, a friend of mine told me to buy a special sandwich gasket, it had an asbestos material to prevent heat from migrating from the manifold to the carb. I had this problem with a mitsubishi and it worked.Now I would have to see if they have this for a 4 barrel. If not I will have to make my own.

MOPAR (Move Over Plymouth Approching Rapidly)

-

73 runner

- Satellite Sebring (RH)

- Posts: 57

- Joined: Sun Feb 06, 2005 6:04 am

- Location: vancouver,bc canada

Well since mine is a 800cfm, and if you drive it normal it gets good gas milage. But my personal view is, the quick start up with the electric choke, and the performance. In reality, to me the gas milage is no real concern. And I like it a lot better than the thermoquad. When I bought the car in 77, [I'am the second owner] it had the 600 Holley. The engine hated it, very poor start up, leaking at the bowls,just lousy performance. In 78, thats when I put the thermoquad back on and the rest is history.

I seem to remember a lengthy thread over on moparts about the edelbrock carbs having the bowls vented and allowing the gas to evap. fairly quickly. I don't believe it's vapor lock. It will start back up within a couple of hours, but longer than that and it takes a lot of cranking. I haven't had the butterscotch car all together for a year and a half....I'll probably just replace the carb when I do...

- luvmoparz

- GTX (RS)

- Posts: 184

- Joined: Thu Sep 21, 2006 3:18 pm

- My Cars: 1972 440 Roadrunner/GTX

- Location: Lake Elsinore

- Contact:

Eric wrote:The car has an intake not suited for the engine right now (torker single plane on a fairly stock engine) which could account for some of the bog? I'll probably end up finding a factory intake and a holley carb

I agree with the Holley option. Had a Edelbrock on my last car....POS! I have a 4150 now but no choke or choke plate for that matter. Have a new Street Avenger in the box.....will install in the spring likely

--------------------------

1972 440 Roadrunner/GTX

1972 440 Roadrunner/GTX

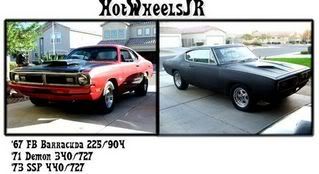

- Hotwheelsjr

- Satellite Sebring Plus (RP)

- Posts: 78

- Joined: Fri Mar 11, 2005 11:17 am

- JosephGiannini

- GTX (RS)

- Posts: 128

- Joined: Tue Oct 21, 2003 9:40 am

- My Cars: 1972 roadrunner 340 4 barrel with 727

- Location: washington dc

Usually with edelbrock carburetors. I run edelbrock manifolds. It is true the torkers and weiands work better with the holleys. But go figure weiand is holley. So usually this is why when you go to a site. Ie holley, weiand, edelbrock you look at the manufacturer suggested package for the engine. And work from there as well as lookign at the original setup.

Did holley come on what engine with what intake etc etc. Me myself I ran holley awesome carburetor for the quarter mile. However for other applications I would go with demon or a edelbrock manifold/carb setup. For most stock applications quadrajet isnt a bad way to go if you get it breathing right and setup right. I think as well as jetting and heads and all to get the motor to breathe right igntion and timing is a factor as well. So to get everything perfect using a cut off wheel and checking the fuel burn rings on the spark plugs is a great way to tell when you got it just right. From the right fuel pump to the manifold to heads etc etc. Most classic car owners want the car running a certian way and this is one way to get it to that perfection we all seek. As well as now both holley and edelbrock offer EFI kits for mopars now if you just want the daily driver feel.

http://www.carcraft.com/techarticles/se ... index.html

Selecting the right carb is not an exact science. No…it’s more akin to nature’s complex tapestry of life, an intricate mosaic of complex variables combining in myriad ways to produce often unexpected results. There is logic and order behind the mystery, but the patterns are not the cut-and-dried solutions of engineering textbooks; instead, they’re derived from the school of real-world experience as learned through trial and experimentation by a leading carburetor expert like Barry Grant, owner and founder of Barry Grant Inc., parent company of Demon Carburetion.

“Formulas Are Useless!â€

Grant doesn’t believe in formulas—and for good reason. Textbooks tell us you can accurately select the proper carburetor size based on a relatively straightforward formula (see the formula at the right) that takes into account engine displacement, max rpm, and volumetric efficiency (VE).

Plugging some actual numbers into the equation, what does it recommend for a 350 engine turning 6,000 rpm at 100 percent VE (see the second formula)?

Formula

CUBIC INCHES/2 x RPM/1,728 x Volumetric efficeincy=CFM

607.6 cfm?! Virtually no one—whether the original equipment manufacturer, aftermarket tuner, or racer—actually installs such a small carb on a high-performance 350. In the real world, everyone knows these engines make more power with larger carbs. Yet dyno-tests show the formula is an accurate reflection of an engine’s airflow needs. The equation breaks down as a realistic carburetor size selection tool because carburetor flow ratings (in cfm, or cubic feet/minute) are taken at an arbitrary vacuum drop—3.0-inches Hg for two-barrels; 1.5-inches Hg for four-barrels—and there’s no guarantee that, at max-rpm wide-open throttle (WOT), any given engine actually sees the theoretical vacuum drop for which the carburetor is rated!

Pulling Vacuum Sucks

On the other hand, if a carb really does pull 1.5-inch-Hg (or more) vacuum at WOT, it has become a restriction. The carb is actually too small to let the engine realize its maximum power potential. That’s because the greater the pressure drop (the higher the vacuum reading) across or through the carburetor, the lower the air density is inside the intake manifold and combustion chamber. Racers like to see no greater than 0.5 to 0.75-inch-Hg vacuum on the top end. But race cars have high-stall converters and steep rearend gears, and most of them are lighter than the average street car. Racers don’t mind recalibrating the carb on the spot for changing track conditions. They are unconcerned about low-end driveability. That’s why all-out racers, when not restricted by the rules, run huge carburetors—the bigger the carburetor, the lower the pressure drop across it at any given airflow.

Driven to Compromise

It’s a different story for street cars and dual-purpose street/strip pack- ages. For these combos, the limiting factor in carburetor size selection is on the low-end side of the fuel curve. Will the carb meter correctly at lower airflows? Will it have good part-throttle driveability in the engine’s normal operating range? How will it drive in the winter, desert, and mountains?

As in life, so it is with carbs: Compromises are called for—a fine balance. Not too big because you’ll lose driveability. Not too small or the carb becomes a major bottleneck. For most hot, dual-purpose cars, pulling about 1.0-inch-Hg manifold vacuum at WOT, max rpm on the dyno isn’t far off. But there are no guarantees. It’s impossible to know for sure how a carb will perform in a vehicle based on how it did on an engine dyno. Every combo behaves differently; what works in a featherweight car with a manual trans and 5-series rear-gears ain’t gonna cut it in a 3,700-pound ride with a mild converter and 3.23:1 rear gears. As Grant puts it, “You’ve got to do lots of empirical work and go through lots of trial and error. It really takes thousands of carbs before you get an intuitive feel for what’ll work on a given application.â€

Grant Us the Knowledge

Fortunately, you don’t have to wait until you’re old and gray to find the answer—you can take advantage of Grant’s gray hair instead. His guidelines are based on years of experience. While they apply specifically to Demon carbs, the general principles are applicable to other carburetor makes as well. The basic parameters revolve around engine load versus engine size as expressed in cubic inches. Compression ratio, vehicle weight, distributor mechanical advance curve, cam duration as it factors into actual running (as opposed to static) compression, trans and converter, and final drive ratio all factor into carb selection.

All things being equal, a bigger engine requires a larger carb. But for any given engine size:

• Higher rpm requires a bigger carb

• Higher horsepower requires a bigger carb

• Higher compression ratios require a bigger carb

• More distributor mechanical advance requires a bigger carb

• A manual-trans car can use a larger carb than an automatic-trans car

• Steeper (higher numerical) rearend gears tolerate a bigger carb

• Lighter cars can use a bigger carb

• Heavy cars need a smaller carb

• Too large a cam for the application requires a smaller carb

• With an automatic-trans car, too low a torque-converter stall-speed for the application requires a smaller carb

• Mild (lower numerical) rearend gears require a smaller carb

• Low compression requires a smaller carb

Specific recommendations for Demon carb selection can be found in the carburetor selection chart (see the "Demon Carburetor Selection Guide" sidebar.

Manifold Destiny

Another important factor influencing carb selection is intake manifold design. With its divided plenum, a typical dual-plane intake provides a stronger signal to the carb than a single-plane manifold. Grant says a 350 Chevy with a dual-plane intake can usually use a 750 carb; if it’s running a single-plane, a 650 carb will probably get the car down the track quicker. One way to crutch a single-plane/large-carb combo suffering from insufficient signal is to use a four-hole carburetor spacer.

Although not recommended, some people just have to run a tunnel-ram on the street. That’s possible with careful tuning and proper carb and manifold selection. Grant reports that two 650s work well, provided you use a manifold with long runners to maintain low- and midrange torque. “Long†in this case means at least 6-8 inches. The larger the plenum volume, the less the signal, and the smaller the carb(s) needs to be.

Secondary Opinions

If you are reluctant to trade top-end performance for all-around driveability, there are several cheats that will allow a larger-than-normal (for the given application and combo) carb to do a satisfactory driveability job. One important method is secondary actuation.

Normally a mild converter, weak rearend gears, and/or a heavy vehicle will call for a smaller carb to retain decent low-end performance. But we know the smaller carb restricts power upstairs. One possible solution: Run the larger carb, but with vacuum (instead of mechanical) secondaries. Vacuum secondaries won’t open until the engine needs the extra airflow. Assuming the vacuum secondaries are properly tuned with the appropriate-tension spring, the engine won’t bog even if you punch the throttle wide-open at low speed. But when there’s sufficient primary airflow to allow the diaphragm to open the secondaries, the engine is ready to accept the extra capacity. Grant says vacuum-secondary carbs work particularly well if running under 3.55:1 gears, the car weighs over 3,500 pounds, or if you have 8.5:1 or less compression.

For just about any other combo, Grant recommends staying with the twin-squirter, mechanical-secondary carb. “If the engine withstands a mechanically actuated secondary without bogging, the rpm will rise quicker and performance will be better than with a vacuum secondary,†says Grant. Note that twin-squirter carbs are much more finicky about proper sizing than the more forgiving vacuum-secondary models, which is why there are more different twin-squirter sizes available in comparison to vacuum-secondary cfm ratings

Booster Shots

Yet another solution to the big carb for power versus smaller carb for driveability dilemma is to use a different-design booster venturi. Demon offers two different styles on some carbs: downleg boosters and annular boosters. Annular boosters are more responsive than downleg boosters. They pick up the vacuum signal quicker and start flowing sooner. While annular boosters offer more bottom-end driveability, they run richer on the top end and may siphon fuel out of the float bowls. The annular booster also decreases the carb’s ultimate airflow potential because it has a larger physical presence within the venturi. For example, the Race Demon 950-cfm carb with annular boosters has the same venturi size as the 1,050-cfm Demon with downleg boosters.

Generally, annular boosters work best on 850-or-larger-cfm carbs to restore bottom-end performance on small-displacement engines or heavy vehicles. On lightweight cars and/or large-cubic-inch engines where bottom-end response isn’t a problem, you’re usually better off with a downleg-style booster.

Integration Now!

Hopefully, the preceding has given you some fuel for thought on selecting the proper-size carburetor. The point to remember is that there is no magic answer; your fuel-metering device must be an integrated member of a total engine, vehicle, and overall drivetrain combo working harmoniously to deliver performance under all desired conditions. Of course, selecting the proper-size carb is just the beginning in the same sense that choosing the right golf club for the next shot is only one small (but necessary) ingredient of getting the ball into the cup.

Whether it’s golf or carburetors, technique and skill are nearly as important as proper equipment selection. So next month we’ll cover the other half of the carburetor equation. Now that you have the right carb in hand, how do you tune and modify it so it can realize its full potential?

Stay tuned!

Hope this helps out!!

Did holley come on what engine with what intake etc etc. Me myself I ran holley awesome carburetor for the quarter mile. However for other applications I would go with demon or a edelbrock manifold/carb setup. For most stock applications quadrajet isnt a bad way to go if you get it breathing right and setup right. I think as well as jetting and heads and all to get the motor to breathe right igntion and timing is a factor as well. So to get everything perfect using a cut off wheel and checking the fuel burn rings on the spark plugs is a great way to tell when you got it just right. From the right fuel pump to the manifold to heads etc etc. Most classic car owners want the car running a certian way and this is one way to get it to that perfection we all seek. As well as now both holley and edelbrock offer EFI kits for mopars now if you just want the daily driver feel.

http://www.carcraft.com/techarticles/se ... index.html

Selecting the right carb is not an exact science. No…it’s more akin to nature’s complex tapestry of life, an intricate mosaic of complex variables combining in myriad ways to produce often unexpected results. There is logic and order behind the mystery, but the patterns are not the cut-and-dried solutions of engineering textbooks; instead, they’re derived from the school of real-world experience as learned through trial and experimentation by a leading carburetor expert like Barry Grant, owner and founder of Barry Grant Inc., parent company of Demon Carburetion.

“Formulas Are Useless!â€

Grant doesn’t believe in formulas—and for good reason. Textbooks tell us you can accurately select the proper carburetor size based on a relatively straightforward formula (see the formula at the right) that takes into account engine displacement, max rpm, and volumetric efficiency (VE).

Plugging some actual numbers into the equation, what does it recommend for a 350 engine turning 6,000 rpm at 100 percent VE (see the second formula)?

Formula

CUBIC INCHES/2 x RPM/1,728 x Volumetric efficeincy=CFM

607.6 cfm?! Virtually no one—whether the original equipment manufacturer, aftermarket tuner, or racer—actually installs such a small carb on a high-performance 350. In the real world, everyone knows these engines make more power with larger carbs. Yet dyno-tests show the formula is an accurate reflection of an engine’s airflow needs. The equation breaks down as a realistic carburetor size selection tool because carburetor flow ratings (in cfm, or cubic feet/minute) are taken at an arbitrary vacuum drop—3.0-inches Hg for two-barrels; 1.5-inches Hg for four-barrels—and there’s no guarantee that, at max-rpm wide-open throttle (WOT), any given engine actually sees the theoretical vacuum drop for which the carburetor is rated!

Pulling Vacuum Sucks

On the other hand, if a carb really does pull 1.5-inch-Hg (or more) vacuum at WOT, it has become a restriction. The carb is actually too small to let the engine realize its maximum power potential. That’s because the greater the pressure drop (the higher the vacuum reading) across or through the carburetor, the lower the air density is inside the intake manifold and combustion chamber. Racers like to see no greater than 0.5 to 0.75-inch-Hg vacuum on the top end. But race cars have high-stall converters and steep rearend gears, and most of them are lighter than the average street car. Racers don’t mind recalibrating the carb on the spot for changing track conditions. They are unconcerned about low-end driveability. That’s why all-out racers, when not restricted by the rules, run huge carburetors—the bigger the carburetor, the lower the pressure drop across it at any given airflow.

Driven to Compromise

It’s a different story for street cars and dual-purpose street/strip pack- ages. For these combos, the limiting factor in carburetor size selection is on the low-end side of the fuel curve. Will the carb meter correctly at lower airflows? Will it have good part-throttle driveability in the engine’s normal operating range? How will it drive in the winter, desert, and mountains?

As in life, so it is with carbs: Compromises are called for—a fine balance. Not too big because you’ll lose driveability. Not too small or the carb becomes a major bottleneck. For most hot, dual-purpose cars, pulling about 1.0-inch-Hg manifold vacuum at WOT, max rpm on the dyno isn’t far off. But there are no guarantees. It’s impossible to know for sure how a carb will perform in a vehicle based on how it did on an engine dyno. Every combo behaves differently; what works in a featherweight car with a manual trans and 5-series rear-gears ain’t gonna cut it in a 3,700-pound ride with a mild converter and 3.23:1 rear gears. As Grant puts it, “You’ve got to do lots of empirical work and go through lots of trial and error. It really takes thousands of carbs before you get an intuitive feel for what’ll work on a given application.â€

Grant Us the Knowledge

Fortunately, you don’t have to wait until you’re old and gray to find the answer—you can take advantage of Grant’s gray hair instead. His guidelines are based on years of experience. While they apply specifically to Demon carbs, the general principles are applicable to other carburetor makes as well. The basic parameters revolve around engine load versus engine size as expressed in cubic inches. Compression ratio, vehicle weight, distributor mechanical advance curve, cam duration as it factors into actual running (as opposed to static) compression, trans and converter, and final drive ratio all factor into carb selection.

All things being equal, a bigger engine requires a larger carb. But for any given engine size:

• Higher rpm requires a bigger carb

• Higher horsepower requires a bigger carb

• Higher compression ratios require a bigger carb

• More distributor mechanical advance requires a bigger carb

• A manual-trans car can use a larger carb than an automatic-trans car

• Steeper (higher numerical) rearend gears tolerate a bigger carb

• Lighter cars can use a bigger carb

• Heavy cars need a smaller carb

• Too large a cam for the application requires a smaller carb

• With an automatic-trans car, too low a torque-converter stall-speed for the application requires a smaller carb

• Mild (lower numerical) rearend gears require a smaller carb

• Low compression requires a smaller carb

Specific recommendations for Demon carb selection can be found in the carburetor selection chart (see the "Demon Carburetor Selection Guide" sidebar.

Manifold Destiny

Another important factor influencing carb selection is intake manifold design. With its divided plenum, a typical dual-plane intake provides a stronger signal to the carb than a single-plane manifold. Grant says a 350 Chevy with a dual-plane intake can usually use a 750 carb; if it’s running a single-plane, a 650 carb will probably get the car down the track quicker. One way to crutch a single-plane/large-carb combo suffering from insufficient signal is to use a four-hole carburetor spacer.

Although not recommended, some people just have to run a tunnel-ram on the street. That’s possible with careful tuning and proper carb and manifold selection. Grant reports that two 650s work well, provided you use a manifold with long runners to maintain low- and midrange torque. “Long†in this case means at least 6-8 inches. The larger the plenum volume, the less the signal, and the smaller the carb(s) needs to be.

Secondary Opinions

If you are reluctant to trade top-end performance for all-around driveability, there are several cheats that will allow a larger-than-normal (for the given application and combo) carb to do a satisfactory driveability job. One important method is secondary actuation.

Normally a mild converter, weak rearend gears, and/or a heavy vehicle will call for a smaller carb to retain decent low-end performance. But we know the smaller carb restricts power upstairs. One possible solution: Run the larger carb, but with vacuum (instead of mechanical) secondaries. Vacuum secondaries won’t open until the engine needs the extra airflow. Assuming the vacuum secondaries are properly tuned with the appropriate-tension spring, the engine won’t bog even if you punch the throttle wide-open at low speed. But when there’s sufficient primary airflow to allow the diaphragm to open the secondaries, the engine is ready to accept the extra capacity. Grant says vacuum-secondary carbs work particularly well if running under 3.55:1 gears, the car weighs over 3,500 pounds, or if you have 8.5:1 or less compression.

For just about any other combo, Grant recommends staying with the twin-squirter, mechanical-secondary carb. “If the engine withstands a mechanically actuated secondary without bogging, the rpm will rise quicker and performance will be better than with a vacuum secondary,†says Grant. Note that twin-squirter carbs are much more finicky about proper sizing than the more forgiving vacuum-secondary models, which is why there are more different twin-squirter sizes available in comparison to vacuum-secondary cfm ratings

Booster Shots

Yet another solution to the big carb for power versus smaller carb for driveability dilemma is to use a different-design booster venturi. Demon offers two different styles on some carbs: downleg boosters and annular boosters. Annular boosters are more responsive than downleg boosters. They pick up the vacuum signal quicker and start flowing sooner. While annular boosters offer more bottom-end driveability, they run richer on the top end and may siphon fuel out of the float bowls. The annular booster also decreases the carb’s ultimate airflow potential because it has a larger physical presence within the venturi. For example, the Race Demon 950-cfm carb with annular boosters has the same venturi size as the 1,050-cfm Demon with downleg boosters.

Generally, annular boosters work best on 850-or-larger-cfm carbs to restore bottom-end performance on small-displacement engines or heavy vehicles. On lightweight cars and/or large-cubic-inch engines where bottom-end response isn’t a problem, you’re usually better off with a downleg-style booster.

Integration Now!

Hopefully, the preceding has given you some fuel for thought on selecting the proper-size carburetor. The point to remember is that there is no magic answer; your fuel-metering device must be an integrated member of a total engine, vehicle, and overall drivetrain combo working harmoniously to deliver performance under all desired conditions. Of course, selecting the proper-size carb is just the beginning in the same sense that choosing the right golf club for the next shot is only one small (but necessary) ingredient of getting the ball into the cup.

Whether it’s golf or carburetors, technique and skill are nearly as important as proper equipment selection. So next month we’ll cover the other half of the carburetor equation. Now that you have the right carb in hand, how do you tune and modify it so it can realize its full potential?

Stay tuned!

Hope this helps out!!

I own a 340 850hp Dick landy industries spec engine god rest his soul.

A Mopar god Is dead.

1972 roadrunner.

A Mopar god Is dead.

1972 roadrunner.

- JosephGiannini

- GTX (RS)

- Posts: 128

- Joined: Tue Oct 21, 2003 9:40 am

- My Cars: 1972 roadrunner 340 4 barrel with 727

- Location: washington dc

Sparkplug tuning

Some track knowledge for the street!!

http://www.carcraft.com/techarticles/sp ... index.html

There’s a lot of mystery and secrecy when it comes to professional level race car tuning. What’s the procedure for determining timing and jetting, and can a change that would be seemingly insignificant in a street car really make the difference between winning and losing? To get some insight into the black magic of tuning, we roped Mr. SplitFire himself, NHRA Pro Stock racer Jim Yates, into explaining the nitty-gritty on how he tunes his Pontiac Grand Am by reading the plugs. And with Pro Stock being as close and competitive as any class in racing, this is truly a place where tuning is key.

This is what Yates’s plug should look like if the fuel mixture and timing are dead on. The Yates team pulls the plugs and examines the ground straps (circle) after every run. The discoloring on the ground strap helps determine whether or not timing needs to be advanced or retarded. If the fuel and timing are where they need to be, the ground strap will display a rainbow-effect discoloration at the base of the strap. If the entire ground strap is discolored there’s too much timing; if there isn’t any at all, then timing is too far retarded.

After two or three passes, a cut-off wheel is taken to the plugs to reveal the porcelain core. Here the Yates team can see how rich or lean the fuel mixture is. The higher the ring (arrow) the fatter the mixture. But after about three passes, the plugs get harder to read and tend to look on the rich side regardless. This particular plug reveals an optimum mixture as verified by Yates’ 6.838 at 201-mph qualifying pass during last year’s NHRA Winston Finals at Pomona.

If the plugs read excessively rich like this one...

the main jets and the air bleeds in the carburetors are changed to lean it out

these readings tell you when to change the jets etc etc

refer to the article for the diagrams for key on point tuning!!

To get that engine running right!!!

Some track knowledge for the street!!

http://www.carcraft.com/techarticles/sp ... index.html

There’s a lot of mystery and secrecy when it comes to professional level race car tuning. What’s the procedure for determining timing and jetting, and can a change that would be seemingly insignificant in a street car really make the difference between winning and losing? To get some insight into the black magic of tuning, we roped Mr. SplitFire himself, NHRA Pro Stock racer Jim Yates, into explaining the nitty-gritty on how he tunes his Pontiac Grand Am by reading the plugs. And with Pro Stock being as close and competitive as any class in racing, this is truly a place where tuning is key.

This is what Yates’s plug should look like if the fuel mixture and timing are dead on. The Yates team pulls the plugs and examines the ground straps (circle) after every run. The discoloring on the ground strap helps determine whether or not timing needs to be advanced or retarded. If the fuel and timing are where they need to be, the ground strap will display a rainbow-effect discoloration at the base of the strap. If the entire ground strap is discolored there’s too much timing; if there isn’t any at all, then timing is too far retarded.

After two or three passes, a cut-off wheel is taken to the plugs to reveal the porcelain core. Here the Yates team can see how rich or lean the fuel mixture is. The higher the ring (arrow) the fatter the mixture. But after about three passes, the plugs get harder to read and tend to look on the rich side regardless. This particular plug reveals an optimum mixture as verified by Yates’ 6.838 at 201-mph qualifying pass during last year’s NHRA Winston Finals at Pomona.

If the plugs read excessively rich like this one...

the main jets and the air bleeds in the carburetors are changed to lean it out

these readings tell you when to change the jets etc etc

refer to the article for the diagrams for key on point tuning!!

To get that engine running right!!!

I own a 340 850hp Dick landy industries spec engine god rest his soul.

A Mopar god Is dead.

1972 roadrunner.

A Mopar god Is dead.

1972 roadrunner.